The secret to maximizing energy, time, and productivity. 2nd in a Series | Part 1, Part 3, Part 4

By Colleen Jordan Hallinan, Qii Consulting

In The Intersection of Self-Care and Achievement we established that walking away from your computer or workspace to do something that seemingly contributes nothing to work, like taking a walk or doing yoga, can be as, or more, productive as powering through in dogged pursuit of completion.

The Nerdy Background

The science behind this is in the brain’s default mode network (DMN). Back in the early 90s, two scientists studying the brain, each using different brain imaging technology, independently discovered that a resting-state brain is only 5% less active than a cognitively engaged brain, and that’s because when we switch from cognitively demanding work to passive rest or mind-wandering, a whole second set of brain regions instantly fire up like an emergency generator.

The DMN has mostly been associated with creativity, some of which is due to findings that it connects different parts of the brain that aren’t usually connected. It’s foundational activity involves “thinking about others, thinking about one’s self, remembering the past, and envisioning the future rather than the task being performed.” This is very fluid, often creative, thinking we know as mind-wandering. As you can likely relate, you’re immersed in it while you’re taking a walk or even while performing a mildly engaging task like mending a sock.

More than 60 years before functional MRIs and PET scans were able to “see” the switch from one set of brain regions to another, Graham Wallas recognized the contribution of the unconscious mind to creative breakthroughs, theorizing an incubation stage which requires real mental relaxation. Wallas mused on whether researching the world’s most creative thinkers and writers would prove it out.

Nearly a century later, Alex Soojung-Kim Pang answered this appeal by examining the work routines of some of the most creative and influential people in history in Rest. The pattern that emerges is how much leisure time these people included in their daily routines. It turns out that extraordinary ingenuity can be carefully and thoughtfully planned for and nurtured with routines that put as much emphasis on rest as they do on intense, deliberate, focus.

“They weren’t accomplished despite their leisure; they were accomplished because of it.” –Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

Four Hours: A Key to Productivity

Henri Poincaré, perhaps the 19th century’s most famous polymath (there doesn’t seem to be an area in mathematics or physics to which he did not contribute) did most of his focused work and thinking from 10-12pm and 5-7pm. Like many other towering geniuses, prolific writers, and scientists, Poincaré was very deliberate about restricting his work to about four hours. Other high achievers Pang reviews, who deliberately planned for leisure as a function of success, include Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, W. Somerset Maugham, Ernest Heminway, John Le Carré, Alice Munro, Scott Adams of Dilbert fame, and Thomas Jefferson.

Apparently, Jefferson used to burn the midnight oil until he discovered “a great inequality” in the “vigor of the mind at different times of the day,” and developed a morning routine of four hours of intense work, a bit more after lunch, and the rest of the day for physical rejuvenation outdoors. And Stephen King, who’s written over 60 novels, declares his schedule is “pretty clear cut. Mornings…are for the current composition…afternoons for naps and letters… Evenings are for reading, family, Red Sox… and revisions that can’t wait.” Ironically, even the guy who created the first residency program for doctors recommended students work a maximum of “four or five hours daily,” if intensely focused.

Your Second Challenge

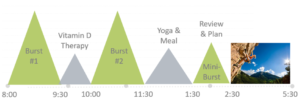

You must be wondering (I have!) how it is possible for these highly productive, creative people to accomplish so much in 4 hours, when our experience mostly consists of 8, 10, or even 12-hour days, and we still feel behind. In the last episode of this series, you were challenged to simply intersperse 90-minute chunks of work with 30-60 minutes of self-care. This time your challenge is to experiment with intentionally designed 4-hour days.

“My value is based on my best ideas in any given day, not the number of hours I work.” –Scott Adams, Dilbert creator

Given we have a finite number of hours in a day and limited stores of energy, which get replenished when we eat, rest, exercise, sleep or simply take a break, it is logical that a routine that fully rejuvenates us would be more efficient, and almost certainly deliver more value. But you tell me, does working less and playing more actually provide the leverage we need to get out from behind the 8-ball? No, really, please, take up the challenge and tell me! Connect and let me know how it goes.